Brown tackles public health issues through the microscope

In September, Hurricane Maria devastated the U.S. island of Puerto Rico, ravaging it with 150 mile per hour winds and more than 20 inches of rain. In the aftermath of the storm, three million people are still without power, and one million are without running water. Contaminated wells and surface water are creating a public health crisis, spreading cholera and diarrheal diseases.

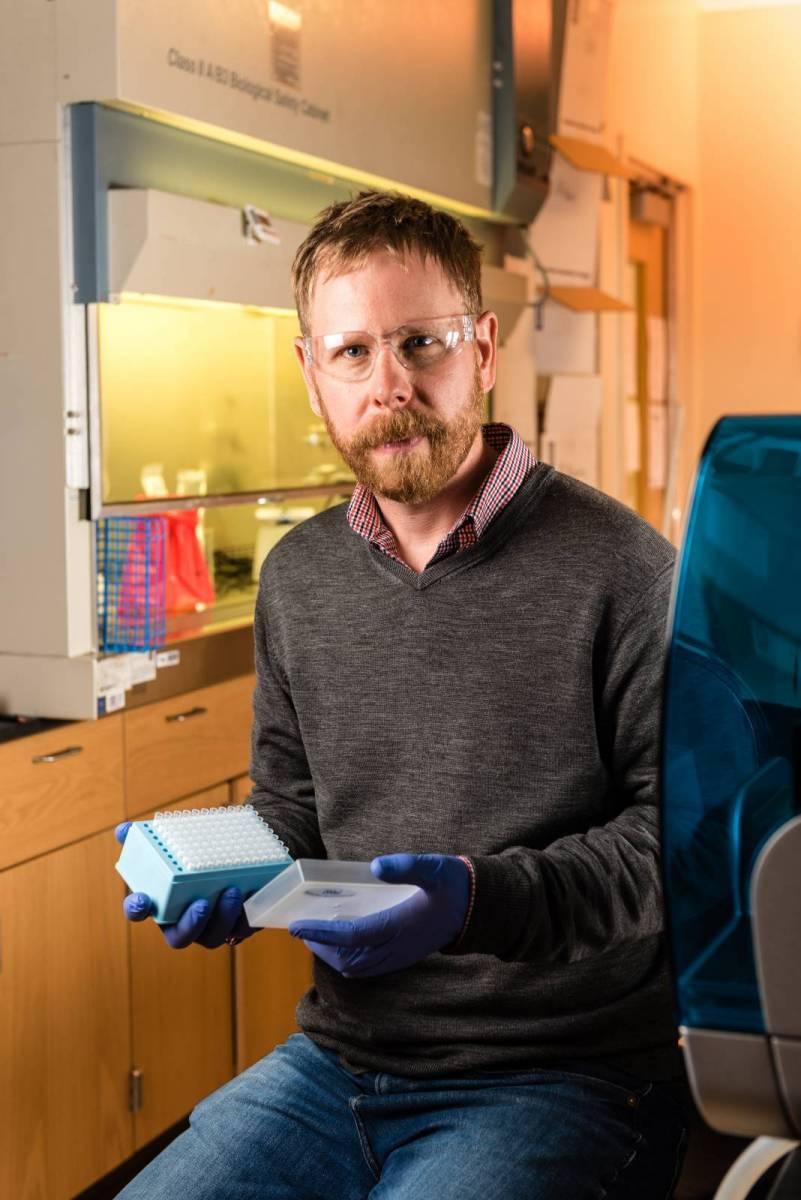

Joe Brown, assistant professor in Tech’s School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, agrees that Puerto Rico faces a number of challenges around microbial exposures following the disaster. Brown studies pathogenic microbial exposures – microscopic organisms that can hurt humans – and sees the most urgent public health issue facing Puerto Rico as the spread of sanitation-related pathogens, including pathogenic viruses, bacteria and protozoa.

“The island’s infrastructure sustained widespread severe damage, so there will be significant challenges to recovery,” said Brown. “Access to safe water is still quite limited in some parts of the island, partly because lack of water pressure leads to contamination of sources. Our studies show that interruptions in water supply can be major causes of disease outbreaks.”

Brown’s research is largely focused on water contamination and its impact on public health. He travels to communities around the world measuring microbes in each environment to gather exposure data and determines what it means for the health and safety of residents. In a recent trip to India, Brown found aerosolized Giardia and Salmonella, pathogens not normally known to be transmitted via air. This discovery creates a new challenge in environmental engineering, one where microbes associated with water and sanitation are transmitted via the air (aerosols), potentially leading to new pathways of disease transmission.

“My current area of focus is around aerosols, meaning the airborne transmission of pathogens, which combines water, sanitation and air quality research,” said Brown. “It’s uncharted territory when it comes to microbial exposures – we know very little about the microbial content of aerosols. This is a new frontier in environmental engineering because before now, we didn’t realize pathogens could move from water to air so easily. It’s a new channel for pathogens to infect more humans and one that needs to be closely studied in the lab.”

Brown’s lab is an environmental health microbiology lab focused on evaluating samples from the field. The team regularly travels to Mozambique and take water, soil, air, flies and stool samples, and bring them back to the lab to look for pathogens. Viewing the samples helps them understand exposure risks. Randomized controls are used to test and measure sanitation programs put in place to combat pathogens. Once technology or infrastructure begins to curtail microbial exposure, the samples are measured again. Then adjustments can be made to the treatment processes, like sanitation technology.

Brown’s latest grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) will allow him to look at enteric pathogen transmission in the air, microbes that move from water and wastewater to air. Enteric pathogens, which affect the gut, can have life-threatening consequences in the developing world where open sewers are commonplace or in storm-ravaged areas like Puerto Rico that lack running water. With this grant, Brown hopes to combat the enteric pathogens by bringing very sophisticated exposure assessment to various communities.

“We are redefining the field by developing and implementing new ways of measuring exposure in pathogen-rich settings,” said Brown. “We are examining how pathogens move through the environment and the impact they have on the health of humans. Our end goal is to prevent disease.”

Brown also recently started a project focused on antimicrobial resistance in partnership with the CDC. Antimicrobial resistance is the ability of a microorganism (like bacteria, viruses, and some parasites) to stop an antimicrobial (such as antibiotics, antivirals and antimalarials) from working against it. As a result, standard treatments become ineffective, infections persist and may spread to others. Brown cites antimicrobial resistance as one of the biggest challenges for public health today, particularly when it comes to pathogens deriving from water or air.

“Antimicrobial resistance related to water and sanitation is a major risk factor associated with the death of children around the world,” said Brown. “So we have to look at environmental exposures and decide how they are linked to human health outcomes. As far as public health problems go, antimicrobial resistance is at the top of that list.”

To improve antimicrobial resistance, Brown says that we must stop using so many antibiotics, particularly in agriculture. Limiting the use of antibiotics and controlling them will slow antibiotic resistance.

“As soon as you find a treatment that’s effective at killing a microbe, it will build a resistance,” said Brown. “Microbes evolve extremely quickly, and many antibiotic resistance genes are widespread in microbial communities already.”

Scientists and researchers must constantly be on the lookout for new ways to fight these microbes, and unfortunately they have billions of years of evolution on their side in terms of their ability to cope.

In Puerto Rico, time is running out for residents, and restoring both power and water is critical to keep pathogenic microbes at bay. Residents are becoming desperate, drinking non-potable water from wells known to be contaminated because the alternative is no water at all. It’s a public health crisis that can’t be ignored, and safe water must be returned to the island as soon as possible to ensure long term health consequences are minimal.