SlothBot, a robot that monitors pollution, temperature and other environmental conditions, survives for 13 months in the tree canopy of the Atlanta Botanical Garden.

Magnus Egerstedt thought his robot would survive a few months. That was the goal when he and his team of Georgia Tech College of Engineering students installed their three-foot SlothBot in the Atlanta Botanical Garden’s tree canopy in May of last year.

But soon, the hot summer days gave way to cooler temperatures and the machine found itself amid leaves colored by fall. SlothBot would successfully endure Atlanta’s chilly winter nights and managed to hang around for its first birthday in the spring. Finally, 13 months after it went up, SlothBot has come down.

“A resounding success,” said Egerstedt, professor and Steve W. Chaddick School Chair in the Georgia Tech School of Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECE). “We showed that our robot can live for more than a year in a challenging environment, on its own, among the elements.”

And well past its expiration date.

A Weekly Surprise

SlothBot, with its big eyes and 3D-printed, fiberglass shell, dangled from a 100-foot cable in the Garden’s 30-acre, midtown Atlanta forest. True to its name, the robot was programmed to move slowly and only when necessary to reach a sunny spot to recharge the batteries. Garden guests would gaze as it crept 50 feet above the ground. All the while, the machine would monitor temperature, weather, carbon dioxide levels and other information.

During its tenure, SlothBot detected the same thing many other instruments around the world found during the Covid-19 pandemic: pollution levels in the Garden dropped as people stayed home and out of their cars for much of 2020. However, those levels were on the rise in the robot’s final months.

A group of Georgia Tech students kept tabs on SlothBot throughout its lifespan. They visited each week for about an hour, bringing the machine down from its perch just inside the Garden’s entrance. They would check motors, make sure batteries were operational and do standard tests.

“It surprised us every week because it still worked,” said Hannah Phillips, who joined the team during the spring semester before graduating with her mechanical engineering degree in May. She’s currently a master’s student. “I learned a lot about mechanical design during my classes, but I learned so much more by getting in the field and studying robotics outside.”

The only hiccup in SlothBot’s stay came in December, when it mysteriously shut down and couldn’t be restarted. ECE Ph.D. student Carmen Jimenez rectified the situation by removing some faulty capacitors and rebuilding its circuits.

“That was a bit of a roller coaster, rushing to get SlothBot back on the wire and working correctly,” said Jimenez. “We’ve been happily surprised by its resiliency ever since.”

A Crowd Favorite

A few weeks ago, Egerstedt, Phillips and Jimenez visited the Garden one final time to ease SlothBot back to the ground. The descension quickly gathered an audience. Guests who had only been able to watch from a distance walked over to touch the machine and see it up close. As the Georgia Tech team carried SlothBot away, families and children called it by name — some even a bit sad to see it go.

“SlothBot has been a tremendous success for both the Atlanta Botanical Garden and Georgia Tech,” said Emily Coffey, the Garden’s vice president of conservation and research. “Over the last year, guests of all ages have adored seeing it hanging in the trees along the Canopy Walk. Our team looks forward to future advances with the technology and how we can utilize what we have collectively learned at the Garden to expand the project to put SlothBot in the wild.”

In addition to being a crowd favorite, SlothBot was also included in the Garden’s high school summer internship program as a way to entice the next generation of roboticists and conservationists.

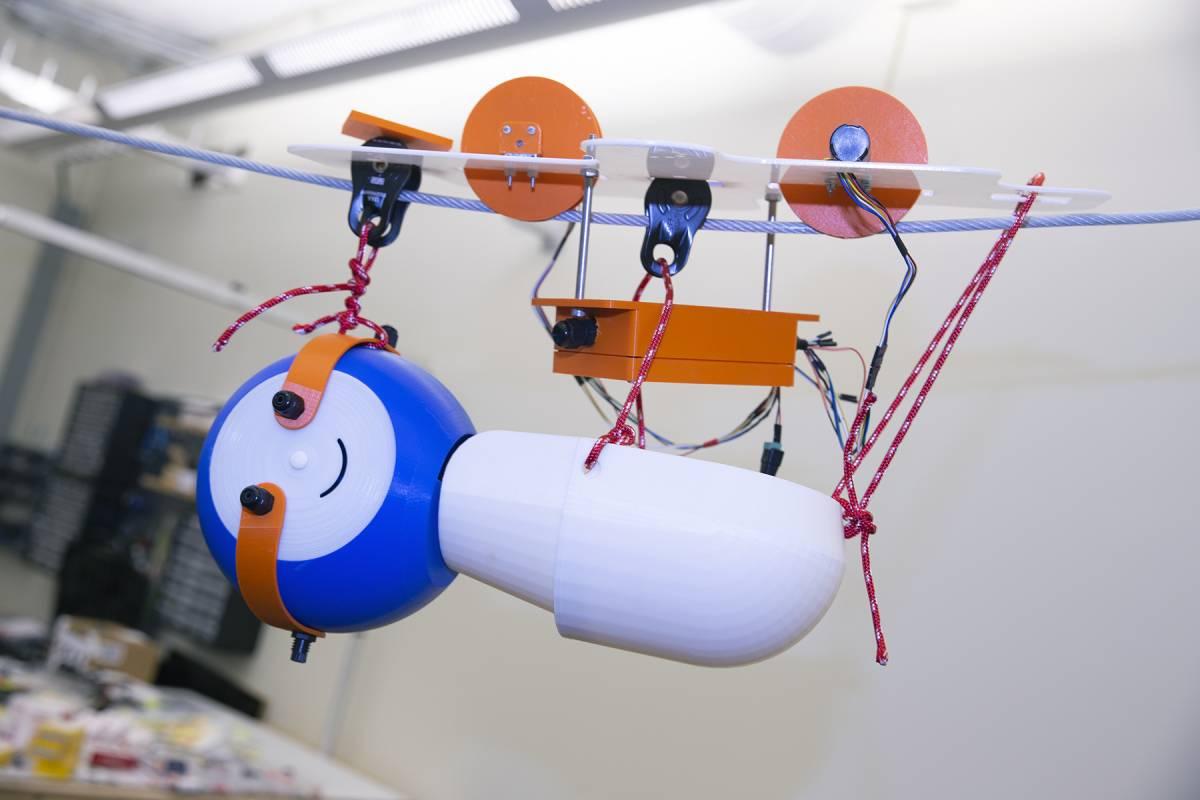

Phillips and Jimenez are using what they’ve already learned to build SlothBot 2.0, which is about half the size of the original and is currently dangling in a Georgia Tech lab.

“We’d like to make the next version more intelligent, capable of interacting with several SlothBots,” said Jimenez. “We’re also trying to make it more nimble and take it from a controlled environment, such as the Garden, and place it in natural ecosystems.”

Its future hang-out is currently a toss-up. While Egerstedt will remain an ECE adjunct professor, he is transitioning to be the dean of engineering at the University of California, Irvine, where he’ll continue the project.

The machine outlived his expectations while also giving him a new outlook on robots and their environment.

“Roboticists typically build machines in the lab and hope they survive in the real world,” said Egerstedt. “But for robots to be able to coexist productively with us for long periods of time, we must treat robots and the environment as a single system. Instead of basing our machines solely on what we want them to achieve, we must consider the constraints of their ecosystems. That’s how we can develop robots that can change and survive in the world we place them in.”

This research was sponsored by the U.S. Office of Naval Research through Grant N00014-15-2115 and by the National Science Foundation through Grant 1531195. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the sponsoring agencies.

RELATED STORY